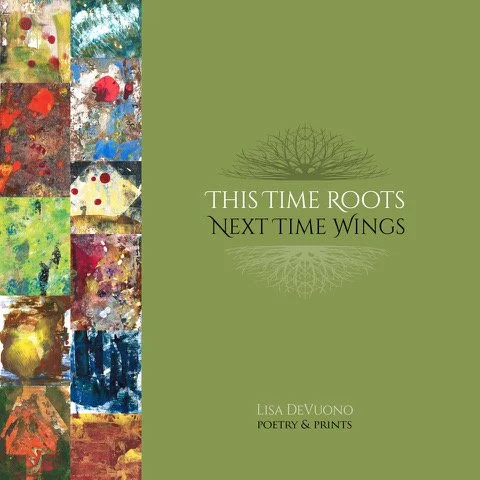

This Time Roots, Next Time Wings

Independently published

$20.00

You can purchase a copy here.

Reviewed by Abbey J. Porter

Lisa DeVuono’s new book, This Time Roots, Next tTime Wings, is a multimedia tour de force that features not only poetry but also short memoirs, family photographs, and images of DeVuono’s paintings. Through this collection, DeVuono engages us in a thoughtful exploration of landscapes both external and internal.

The first thing I noticed about Roots was its physical presence. Square in shape, the volume has a substantial heft at 162 pages. The color printing and satin finish of the pages contribute to the impression of a book produced with great care.

The collection is divided into five thematic sections. The early poems describe the people in the young narrator’s family and the places and customs—both Italian and American—of her youth. Sprinkled among the poems and prose are black and white photos of several of the family members mentioned. Family seems to anchor DeVuono’s narrator; referring to her grandmother coming from Italy for a visit, she says, “Finally I had proof that I came from somewhere.”

But our narrator is caught between worlds, both rooted and rootless. This phenomenon is captured beautifully in the essay “Torrone,” in which DeVuono writes about eating candy sent to the U.S. by relatives in Italy: “The part I felt most hungry for was the tiny sliver of wafer on the edges of the marble-hard torrone. It felt like a veil between two worlds.” The “veil” she speaks of seems to connect—or separate—her Italian ancestry and her American life.

“Hometown Psalm” burgeons with detail about the narrator’s Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood:

Praise to Ray’s penny candy, Charlie’s delicatessen

Melrose Pharmacy and Louie’s Chinese Laundry

to Frank the mailman, our crossing guard Mrs. Ritaldo.

Much as she seems intimately ingrained with her surroundings, she remains someone who is “looking for home.”

We get the sense in several poems of a young woman in peril. “Lifesavers” describes how poets and songwriters save her—from sadness, from fury. The poem concludes:

I have kept an old binder with onion skin paper

where my childhood hand copied their words…

a hand scribbling not softly at all

but raging every day after one injustice or another,

Big Red Chief notebook and fountain pen

where I wrote a first line to save my young life.

The poem is one of several pieces that touch on the role of poetry in the narrator’s life. In the memoir “Fourth Grade Muse,” in which DeVuono describes abuse by the nuns teaching at the narrator’s school, she also finds solace in poetry and pens the line, “Roses are red, violets are blue, the grass is green, how can I hide so I’ll never be seen?”

We accompany the narrator as she grows older. Aging, change, and loss all emerge as themes. So too do physical and mental illness, appearing as opponents the narrator must contend with. In “Severed,” a sort of essay/chant, she reflects,

As she lies here curled up in a fetal position, the neurologist prepares his 12 inch needle poised to extract her cerebrospinal fluid. It occurs to her that she wants to beg him to slip, accidentally move too far to the right or to the left and finish what has already started. Sever the spinal cord, separate her head from her heart, make it official. Then when she faces her own numbing day by day, month by month, she will have no excuse for her lack of pleasure or passion. She can blame him and not this invisible disease that no one really sees.

Perhaps our narrator’s greatest ongoing challenge is the search for self, the attempt to carve out self-identity as she experiences herself in different settings and situations.

In “Bones,” in which she works in the garden, she says, “I weep to find my own bones, a fragile skeleton of all my old selves/Joyous from a slumber I didn’t expect to wake from.” The lines convey a sense of self-discovery, and perhaps redemption.

Part III features the author’s textured, moody, evocative paintings, each one paired with a piece of writing of the same title. The narrator’s mother, a recurring figure throughout the book, appears here in one of my favorite poems, “Ghost.” In this poem, it seems, the narrator is trying to negotiate her mother’s dementia, which has caused her mother to forget who her daughter is. The narrator seeks to create

a swaying rope bridge

where our collective memory might hold us

in the middle of this uncertain footing

where illumination of love might shine

In the haunting conclusion of the poem, the narrator decides,

I must forget who we’ve been

get small again

like a child in the dark

shining a flashlight to my face

“See Momma, I’m the ghost.”

The theme of death—which runs as an undercurrent in the earlier sections of the book—emerges fully in the collection’s fourth section. In “After,” which deals with the aftermath of a death, DeVuono captures the inexpressibility of grief when she refers to “a sentence too long to write.”

The author’s thoughtful, reflective writing invites us to accompany her on the many journeys encompassed in this far-reaching book. DeVuono’s narrator ultimately emerges as quietly heroic from the struggles she faces—struggles that, I suspect, will ring true and familiar to most readers—for the fact that she continues the fight and finds in it moments of grace.

Abbey J. Porter writes poetry and memoir about people, relationships, and life struggles. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte, an MA in liberal studies from Villanova University, and a BA in English from Gettysburg College. Abbey works in communications and lives in Cheltenham, Pa., with her two dogs. You can visit her online at abbeyjportercomms.com.