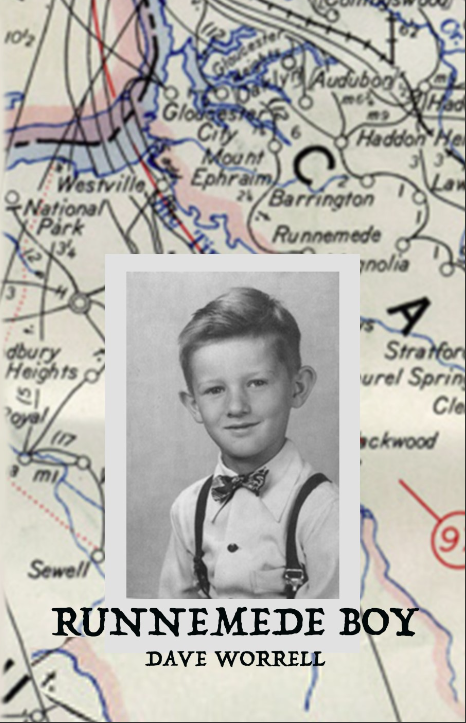

In his recently published book Runnemede Boy, poet Dave Worrell takes us on a journey back in time, into his childhood in Runnemede, New Jersey, in the 1950s and ’60s. In a series of verbal sketches, Worrell gives us a glimpse of those formative elements: interactions with family, the rituals of youth, the moments that can shape a life.

Worrell uses archival material to good effect. In the opening poem, aptly named “Snapshots,” he concludes the description of several childhood photos with a quote from his first-grade report card:

David daydreams now and then,

but comes back to us when we really need him.

He could use more practice carefully

coloring inside the lines.

Worrell does not interpret these lines for us but rather leaves his readers to make of them what we will. This technique is typical of the minimalist style he employs throughout the collection, and it resurfaces in “Dare You…I Dare You.” In this poem, he describes being driven to a Cub Scouts meeting and on the way seeing “two kids jumping/real hard on the frozen lake.” What follows is a series of fragments that seem representative of the nature of memory: hearing sirens, running down the lake, one of the kids’ older brothers diving in to try to save them. Ultimately, one child drowns. Worrell ends with:

Mrs. Di Ciano took us back

to the meeting. Then we went

to the woods on a nature hike.

What he doesn’t say is as powerful as what he does.

Worrell’s style is matter-of-fact. One gets the sense of someone making an honest examination of the past and its artifacts, with the goal of discovering something.

He shares details of the memories that snag in a child’s mind—such as in “A Boy’s First Big League Game.” The narrator accompanies his father, grandfather, and two uncles to a baseball game at Connie Mack Stadium in North Philadelphia. After the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson gets a triple and the Phillies lose, a car full of people passes the narrator’s group, the driver smiling in his Dodgers cap.

Load ’a coal, Pop-Pop snarls.

Uncle Joe laughs. So does Uncle Bruce.

I turn to my father. He isn’t laughing.

He looks me straight in the eye,

shakes his head side-to-side and says No!

The others stop laughing, quiet down.

It’s not the only poem that touches on race. “Runnemede in the ’50s” opens with the statement, “There were no Black families in our town.” The narrator recounts how, when he was 4, his mother took him to Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia to see Santa Claus.

I asked out loud what was the matter

with those people, their skin. My mother

said God makes people in lots of colors.

The nearest Black woman smiled at me

but nobody else said or did anything.

Contemplating the seeming simplicity, yet profundity, of this moment—of this poem—I can’t help but compare it to the fraught state of today’s race relations.

These poems tend toward the straightforward, yet they also explore some of the subtleties of the human psyche. Such is the case with “Getting Right,” in which the narrator fails to protect another, smaller student from harassment by Lydon, “the rich kid in town.” The narrator doesn’t “feel right” until the next week

when I punched Calabrese in the mouth,

knocked out a tooth. Somebody said

he’d been saying stuff about Sharon.

We understand that the rumor about Calabrese is an excuse, that in his violent action, our speaker is attempting to work something out within himself.

Worrell stares at his past with a sort of clear-eyed bravery, writing about behavior (if one assumes the poems to be autobiographical) that he seems to look back on with guilt, shame, and regret. In “Shame,” the narrator steals money from his mother to buy baseball cards, and she finds out. In “I Should Have Turned Out Better,” he wonders, from the distance of age, why he had found it amusing to pick on another student.

The poems also relay the narrator’s first curious, awkward sexual experiences with girls. One of my favorites is “It Never Entered My Mind,” a gently nostalgic piece that recounts a relationship with a girl named Athena: “The ripe, flagrant ones usually snared me/but Athena always was nearby too.” He concludes: “We swapped books: Orwell and Salinger and Eliot/but it never entered my mind to ask her out.” To me, this poem captures the tender regret with which I know I look back on many episodes of my past.

This 46-page collection is an easy, accessible read, and you don’t have to have grown up in a small town in South Jersey to recognize the roads that Worrell travels. Just as the writer may be haunted by some of what he shares in this volume, you may find yourself inhabited by this arresting work.

Abbey J. Porter writes poetry and memoir about people, relationships, and life struggles. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte, an MA in liberal studies from Villanova University, and a BA in English from Gettysburg College. Abbey works in communications and lives in Cheltenham, Pa., with her two dogs. You can visit her online at abbeyjportercomms.com.