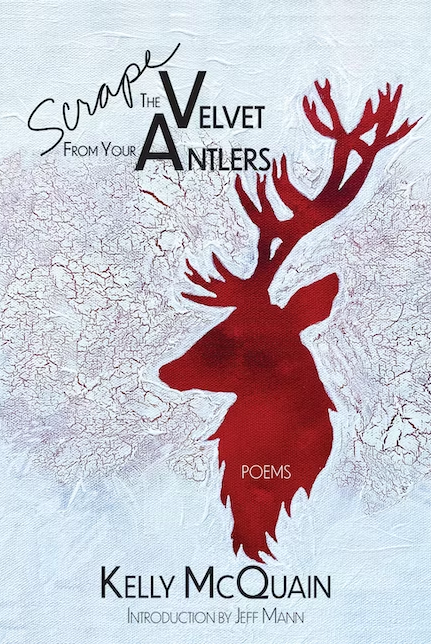

Scrape the Velvet from Your Antlers

Texas A&M University Press

$21.95

You can purchase your copy here.

Reviewed by Sean Hanrahan

The language in Kelly McQuain’s Scrape the Velvet from Your Antlers is layered, evocative, rich, and, at times, either velvet-soft or bone-hard. It is no wonder that this outstanding collection was selected as part of the TRP Southern Poetry Breakthrough Series, which “highlights a debut full-length collection by emerging authors from each state in the southern United States.” Scrape the Velvet from Your Antlers represents the state of West Virginia. It is a well-deserved accolade for this powerful book that explores themes such as the sui generic construction of a queer identity, family relationships, the power of language itself, love, and memory in four sections.

The first section titled Ex Nihilo (Latin for out of nothing) explores the speaker’s creation of a queer identity in the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia. One of the standout poems in this first section is the title poem where the speaker describes himself using some of the fauna found nearby:

You are Joe-Pye weed and yarrow root,

resolute with purpose, pinioned for sky?

Why then is your skin nothing but cockleburs?

Who fiddled with you—rewired deference

into difference? What if you never meet

the person you are meant to be?

The poem’s tonal shift from an uplifting skyward exuberance to a down-to-earth and painful contemplation is the breathtaking work of an immensely skilled poet. In the final stanza, the speaker wonders where he will be able to find his “authentic self.” The answer is eloquently “Not on this hill, not in that house./ Something calls you somewhere else.”

“Uncle,” a tripartite poem in the second section The Grieving Bone, casts a penetrating light on the speaker’s complex relationship with his family, in this case, his brother. “My brother phones to ask a favor/…So I was wondering, if you’d like, maybe,/ donate some sperm—an idea he tosses out/ like bathwater.” This request leads the speaker to consider procreation: “Is it right to create something/ that can be taken away”? and in the second part of the poem, sperm itself:

I looked at my spunk under a microscope once…

I felt as close to that roommate as a brother,

told him what a Catholic schoolgirl once said,

how each time a boy masturbates “he spews death

on countless millions” and we laughed at all the times

we’d pleasured ourselves through mass genocide.

In the final part of “Uncle,” after the speaker has visualized being both father and uncle to a potential child, he is informed by his brother: “False alarm./ He switched to boxers.” Their relationship goes back to what it was “ghosting through each other’s lives.” McQuain ends this powerful meditation with the lines

Sometimes I see children—

older brothers. The way they wrestle,

bodies sweaty, getting knotted,

steeped in tensions and smells

—armpits, peanut butter, sour milk—

until, with a twist, one gets the upper hand:

stronger pins weaker, makes him cry uncle.

“Mechanical Bull” in the third section Bite and Balm is love drunk with the sounds and meanings of language itself. It is a whimsical and humorous poem that successfully sustains an insect metaphor throughout.

Tonight he feels the need for a strange word

in his head: lepidopterist perhaps…

This queer honky-tonk he’s come to

verges on colony collapse disorder

and he is wingless, friendless

whiskeyed thoughts abuzz

While riding a mechanical bull, the speaker’s thoughts and observations on words grow more frenzied in time to the buckling:

Somewhere a lone moth slo-mo struggles

beneath a chloroform cloth, while our rider

puffs his spirit, holds on, clings to strange airs;

he crams his brain with ten-dollar words;

oleaginous (covered in grease),

batrachophagous (eater of frogs).

This poem is a tour de force and evidence of McQuain’s use of line breaks, meter, and diction to create a comic and melancholic effect.

For the final section of the book Tin Hearts, I decided to highlight the gorgeous poem, “Memory Is a Taste that Lingers on the Tongue.” The speaker and a presumed lover visit St. John in the US Virgin Islands, and he recalls

Down to town we drove: the docks

of Cruz Bay beleaguered by tourists; the streets

bottlenecked with cars from the ferry

spilling past whitewashed shops and houses

drowning in late sun and the purples and pinks

of frangipani, bougainvillea, hibiscus.

On the docks, they meet a “bare-chested fisherman” who is gutting a red snapper while another one’s gills were still “fishing against the world’s air.” They both the fish and had a romantic dinner as the poem ends “Even now I can taste that red snapper in my mouth.”

Scrape the Velvet from Your Antlers is a magnificent debut full-length collection from Kelly McQuain, who previously has written chapbooks entitled Velvet Rodeo and Antlers. I highly recommend you check the work of this lyrical, insightful, and clever poet out. Buy a copy for yourself, but a copy for a friend. You will not regret the time spent in McQuain’s company.

Sean Hanrahan is a Philadelphian poet originally hailing from Dale City, Virginia. He is the author of the full-length collection Safer Behind Popcorn (2019 Cajun Mutt Press) and the chapbooks Hardened Eyes on the Scan (2018 Moonstone Press) and Gay Cake (2020 Toho). His work has also been included in several anthologies, including Moonstone Featured Poets, Queer Around the World, and Stonewall’s Legacy, and several journals, including Impossible Archetype, Mobius, Peculiar, Poetica Review, and Voicemail Poems. He has taught classes titled A Chapbook in 49 Days and Ekphrastic Poetry and hosted poetry events throughout Philadelphia.